Expressing obligation in Hebrew - part 2

8 December 2018

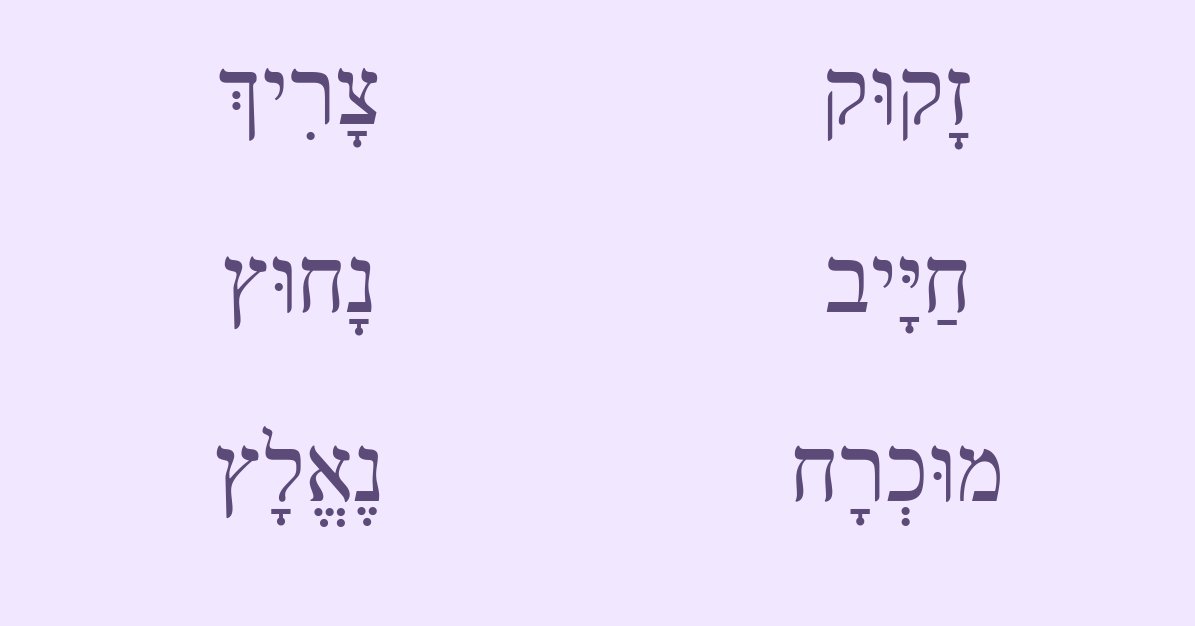

As you have seen in the first part, the concepts "I owe" or "I am obliged to" can be expressed using the words , , , all related to chov – "debt" – and chova "debt", "duty" or "obligation" – as well as the verbs of the same root (). These include ~ לחייב lechayev "to oblige" and ~ להתחייב lehitchayev ("to commit, to undertake").

"Yes, we are going to the store. The situation obliges".

"What you just said obliges me to marry her."

"This obliges him to hold back".

- "I'm not obliged to clean the whole house." (It means: didn’t commit himself to do it).

hitchayavta? - Ta’ase! "In for a penny, in for a pound"! (lit. "If you undertook you should do it")

When the speaker says: или , or the same in the passive voice - - meaning "They made me (or forced me to) go to the store", he usually implies that he has already done what he is talking about.

But if the speaker uses expressions like chiyvu oti / chuyavti, or kafu alay - "I was forced", nichpa alay - "I was imposed", that assumes that the obligation exists but it doesn't necessarily mean that the speaker has already fulfilled it:

(note the use of the preposition and the infinitive)

(note the use of the preposition and the verbal noun).

The verb is also used in banking, meaning “to debit”: lechayev et ha-cheshbon “to debit the account”. This concept is also related to the word .

The same word means “to charge” or “to find guilty” in the legal context. In this sense, it’s opposite to the verb lezakot - to acquit or to drop charges.

A related expression is also used when speaking about judgement – though not in the legal sense:

To judge someone unfavourably, or to see the negative side, is ladun ... le-chaf chova* - that is, to be inclined towards the “cup (or pan) of debt” (as if speaking about the pans of the metaphorical scales of justice).

The opposite, to judge someone favourably, or to see the positive side, is *!לדון לכף זכות ( zchut - "right, privilege ").

The words "to find guilty", chayav "guilty" have the same root. The words of the opposite meaning - lezakot "to find not guilty, to justify", zakay "innocent; entitled (to something)", zchut "right, privilege" – also have the same root ().

In the passive voice, the verb (he was obliged, he is obliged, he will be obliged) can be used instead of ~ לחייב lechayev.

This word, especially in the form of the participle (it is also a form of the present tense), mechuyav - mechuyevet - mechuyavim – mechuyavot, if it is followed not by infinitive but by the noun with a preposition, usually indicates a voluntary undertaking (such as - "I have to/I was obliged to go to the store"), and the noun with the preposition , usually indicates a voluntarily undertaken duty that implies action rather than just proclamation.

The word ~ מחויבות mechuyavut is used in the same context, followed by a noun with the preposition . The best equivalent for these words is “to commit to”, “committed to”, “commitment to something”.

For example: if the municipality spokesman claims:

,

that means that the municipality is committed to improving the living conditions of the inhabitants of the city (and acts towards achieving this goal). Or, alternatively: "We stand for improving the citizen’s living conditions."

~ חייב chayav (chayevet, chayavim, chayavot) - can mean not only “must” or “ought to”, but also "owes, is obliged to" (LondonBoroughof_Hackneycf. - "duty, obligation"). This word also implies a debt, not necessarily monetary, which is the meaning of the word ("debt, arrears"). Moreover, both words have the same plural form - , but one of the words is feminine, while the other one is masculine.

- "he owes you a favour”

- "You owe us a story of the night when you were alone with the Princess of Monaco".

And, of course, monetary debt: - "Paco owes Miguel 50 pesetas".

The verb kafa, mentioned above, means "to impose something on someone" (not to be confused with kafat, “to tie, to entangle”, despite the fact that their infinitives sound the same lichpot. The other forms are not generally the same, and in the infinitives, if you look closely, have different nikkud for "o").

- "friends made Hezi (lit. imposed upon Hezi) go to the store".

The noun (kfiya) - "coercion, domination, brutality ". (kfiya mishtartit) - "police brutality".

Another notable expression: kfuy-tova, kfuyat -tova, kfuyey-tova, kfuyot-tova| is an example of construct state (smichut), with a participle going first instead of a noun. The meaning is “an ungrateful man”. The passive participle kafuy from the verb describes a person who will do no favour ( tova without being forced to.

The verb ~ לאכוף le'echof "to impose, to enforce" – is close in its meaning (and shares two radicals) with the previous one. For example the expression “the law enforcement” translates into Hebrew as .

But in the literature, this verb can be found in the simple meaning of "to force", and then it becomes synonymous to .

- achaf alay ki achabdehu - "he forced me to admire him"

(or, rather, “he really forced one to admire him” - this is a line from Avraham Shlonsky’s translation of Eugene Onegin.)

In instructions and manuals you can find the word yesh with a meaning “one should”, “it is necessary”. It means “have to” (do something). Consequently ein - "Do not have to".

- you have to shake the bottle well before drinking.

- “do not bring the product closer to open flame”.

In the literary language, the preposition with pronominal suffix can be used in the same meaning:

~ עליי alay - "I have to, I should";

~ עלייך alayich - "you (f. sg.) have to, you should"... and so on.

- "he should go to the store, and she should shake the bottle all the time, until he returns".

By the way, if an expression is literary, it does not mean that you will never need it. For example, if you write a letter to an unfamiliar person who is older than you or to somebody important, you can use such expressions as a sign of respect – which you wouldn’t normally use when you drive away your children from the kitchen ().

When used in the negative, expressions of obligation usually mean just an absence of obligation. means “does not have to” rather than "shouldn't". - means “not obliged to” or “not necessarily”.

If we want to turn a simple "no need" into a prohibition or a warning, we can use other expressions:

- "You can’t go to this store!".

- "Do not try to go to this store, in any case!".

You can also use the particle al (which usually means "don't!") with the preposition :

- al lecha lalechet la-chanut hа-zot - "You shouldn't go to that store (don't even think)!".

Modern Hebrew has enriched the sphere of duty and obligation with the word amur ( amura, amurim, amurot), the passive passive participle of the verb amar,. "say". The first meaning אמור is "to be said", and also "mentioned above". ka-amur - "as mentioned above".

In its second meaning, the word means something like: one is supposed (meant, thought, known...) to do smth.

- "yesterday you were supposed to call me!”

It sounds more polite than the direct or .

It is frequently used ironically:

- "What’s this supposed to mean?"

Similarly, you can use the word tzafuy ( tzfuya, tzfuyim, tzfuyot), "expected, anticipated, supposed", ( - "He is expected to contact us") – though it expresses probability rather than obligation.

If you want to politely suggest someone doing something or ask whether you need to do something, then you can use the future tense, or she- with the future tense.

- "Shall we dance?"

- "Why don’t we dance".

- "Shall I open the window?".

There are no verbs of obligation or necessity in these examples but the grammatical structure itself conveys it, just like the word “shall" does ("Shall we dance?")

An infinitive can also be used in this context:

See also

Expressing obligation in Hebrew - part 1